Treaty of Brest-Litovsk

- Not to be confused with the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk (February 9, 1918), a similar treaty involving Ukraine and the Central Powers.

| Treaty of Brest-Litovsk | |

|---|---|

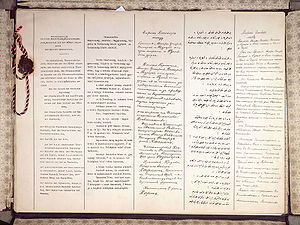

The first two pages of the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk, in (left to right) German, Hungarian, Bulgarian, Ottoman Turkish and Russian

|

|

| Signed Location |

1918 March Brest-Litovsk, Russia |

| Signatories | |

| Languages | Bulgarian, German, Hungarian, Russian, Turkish |

The Treaty of Brest-Litovsk was a peace treaty signed on March 3, 1918, at Brest-Litovsk (now Brest, Belarus) between the RSFSR and the Central Powers, marking Russia's exit from World War I.

While the treaty was practically obsolete before the end of the year, it did provide some relief to Bolsheviks who were tied up in fighting the civil war and affirmed the independence of Finland, Estonia, Latvia, Ukraine, and Lithuania. In Poland, which was not mentioned in the treaty, its signing caused riots and protests, and the final withdrawal of any support for the Central Powers.[1].

Contents |

Armistice negotiations

Peace negotiations began on December 22, 1917, a week after the conclusion of an armistice between Russia and the Central Powers, at Brest-Litovsk (modern Brest, Belarus, near the Polish border). The Germans were represented officially by Foreign Secretary Richard von Kühlmann, but the most important figure in shaping the peace on the German side was General Max Hoffmann, Chief of Staff of the German armies on the Eastern Front (Oberkommando-Ostfront). Austria-Hungary was represented by Foreign Minister Ottokar Czernin, and from the Ottoman Empire came Talat Pasha. The Germans demanded the "independence" of Poland and Lithuania, which they already occupied, while the Bolsheviks demanded "peace without annexations or indemnities" — in other words, a settlement under which the revolutionary government that succeeded the Russian Empire would give neither territory nor money.

The peace delegations that met at Brest-Litovsk were a very mixed assembly. On the one hand there were highly conservative representatives and noblemen from the monarchic German Empire and Austria-Hungary and on the other side were representatives of a radical revolutionary government that had never been seen before in the world and that openly proclaimed the aim of World Revolution. The first impressions after a common dinner were ambivalent. Count Ottokar Czernin, leader of the Austro-Hungarian delegation later wrote:[2]

The leader of the Russian delegation is a Jew, named Joffe, who has recently been released from Siberia [...] after the meal I had a first conversation with Mr. Joffe. His whole theory is simply based on the universal application of the right of self-governance of nations in the broadest form. The thus liberated nations then have to be brought to love each other [...] I advised him that we would not attempt to imitate the Russian example and that we likewise would not tolerate a meddling in our internal affairs. If he continued to hold on his utopic viewpoints the peace would not be possible and then he would be well advised just to take the journey back with the next train. Mr. Joffe looked astonishedly at me with his gentle eyes and was silent for a while. Then he continued in an for me ever unforgettable friendly - I would even nearly say suppliant - tone: "I very much hope that we will be able to raise the revolution also in your country."

The German state secretary Richard von Kühlmann noted:[3]

The Moscovites had a woman as a delegate - of course simply for propaganda reasons. She had shot a Governor who had been unpopular among the Leftists, and was not sentenced to death but to life-long imprisonment due to the mild Tsarist practise. This person, who looked like an elderly housekeeper, Madame Bizenko, apparently a simple-minded fanatic, detailed to Prince Leopold of Bavaria who sat next to her at the dinner table how she conducted the assault. She demonstrated with the menu card in her left hand how she handed a petition to the General Governor—"he was an evil man," she explained—and shot him from beneath the petition with a revolver in her right hand. Prince Leopold listened in a friendly way, as if vividly interested in the murderer's story.

The later leader of the Soviet delegation, Leon Trotsky later reported:[3]

I met with this sort of people for the first time. It is unnecessary to emphasize that I had no illusions about them. But I admit that I had expected the level to be higher. The impression of my first meeting could be summarized in the following statement: These people do not have a high estimation of their counterparts, but they also do not have a high estimation of themselves.

It is important to note that these negotiations were taking place about nine months after the United States had declared war on Germany, but before the Americans were making a significant contribution on the Western Front. The Bolsheviks likely believed that the Germans would seize the opportunity to make a separate peace with Russia (even on moderate terms) so that they would have an opportunity to defeat France and Great Britain before the Americans arrived, even if this meant they would have to settle for less generous terms.

Frustrated with continued German demands for cessions of territory, Leon Trotsky, Bolshevik People's Commissar for Foreign Relations (i.e., Foreign Minister), and head of the Russian delegation, on February 10, 1918, announced Russia's withdrawal from the negotiations and unilateral declaration of the ending of hostilities, a position summed up as "no war — no peace".

Denounced by other Bolshevik leaders for exceeding his instructions and exposing Bolshevist Russia to the threat of invasion, Trotsky subsequently defended his action on the grounds that the Bolshevik leaders had originally entered the peace talks in the hope of exposing their enemies' territorial ambitions and rousing the workers of central Europe to revolution in defense of Russia's new workers' state.

Resumed hostilities

The consequences for the Bolsheviks were worse than what they had feared the previous December. The Central Powers repudiated the armistice on February 18, 1918, and in the next fortnight seized most of Ukraine, Belarus and the Baltic countries. Through the ice of the Baltic Sea, a German fleet approached the Gulf of Finland and Russia's capital Petrograd. Despite strikes and demonstrations the month before in protest against economic hardship, the workers of Germany failed to rise up against the government. On March 3 the Bolsheviks agreed to terms worse than those they had previously rejected.

Terms of the peace treaty

The treaty, signed between Bolshevik Russia on the one side and the German Empire, Austria-Hungary, Bulgaria and Ottoman Empire (collectively the Central Powers) on the other, marked Russia's final withdrawal from World War I as an enemy of her co-signatories, fulfilling, on unexpectedly humiliating terms, a major goal of the Bolshevik revolution of November 7, 1917.

In all, the treaty took away territory that included a quarter of the Russian Empire's population, a quarter of its industry [4] and nine-tenths of its coal mines.[5]

Germany's defeat in World War I, marked by the armistice with the Allies on November 11 at Compiègne, made it possible for Finland, Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Ukraine, and Poland to become independent sovereign states. The designated monarchs had to renounce their thrones.

Transfer of territory to Germany

Russia's new Bolshevik (communist) government renounced all claims on Finland (which it had already acknowledged), the future Baltic states (Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania), Poland, Belarus, and Ukraine. Most of these territories were in effect ceded to the German Empire, which intended to have them become economically dependent on and politically closely tied to the empire under various German kings and dukes.

Regarding the ceded territories, the treaty stated that "Germany and Austria-Hungary intend to determine the future fate of these territories in agreement with their populations". In fact Germany appointed aristocrats to the new thrones of Finland, Latvia, and Lithuania.

Occupation of the ceded territories by Germany required large amounts of manpower and trucks, and yielded little in the way of foodstuffs or other war material. The Germans transferred hundreds of thousands of veteran troops to the Western Front as rapidly as they could, where they started a series of spring offensives that badly shocked the Allies. Some Germans later blamed the occupation for significantly weakening the Spring Offensive.

Transfer of territory to the Ottoman Empire

At the insistence of the Turkish leader Talat Pasha, all lands Russia had captured from the Ottoman Empire in the Russo-Turkish War (1877–1878), specifically Ardahan, Kars, and Batumi, were to be returned. This territory was under the effective control of the newly established Democratic Republic of Georgia and the Democratic Republic of Armenia until 1921. After the Soviets conquered these republics, the territory under Armenian control, by and large, went to Turkey; whereas the territory under Georgian control mostly reverted to the Soviet Union after Georgia's fall in March 1921.

Paragraph 3 of Article IV of the treaty states that:

"The districts of Erdehan, Kars, and Batum will likewise and without delay be cleared of the Russian troops. Russia will not interfere in the reorganization of the national and international relations of these districts, but leave it to the population of these districts, to carry out this reorganization in agreement with the neighboring States, especially with Turkey."

Protection of Armenians' right to self-determination

Russia supported the right of the Armenians in the Ottoman Empire and Russia to determine their destiny, by ensuring the conditions necessary for a referendum:

- The retreat (within 6–8 weeks) of Russian armed forces to the borders of the Democratic Republic of Armenia, and the formation in the ADR of a military power responsible for security (including disarming and dispersing the Armenian militia). The Russians were to be responsible for order (protecting life and property) in Ardahan, Kars, and Batumi until the arrival of the Ottomans.

- The return by the Ottoman Empire of Armenian emigrants who had taken refuge in nearby areas (Ardahan, Kars, and Batumi).

- The return of Ottoman Armenians who had been exiled by the Turkish Government since the beginning of the war.

- The establishment of a temporary National Armenian Government formed by deputies elected in accordance with democratic principles (the Armenian National Council became the Armenian Congress of Eastern Armenians, which established the Democratic Republic of Armenia). The conditions of this government would be put forward during peace talks with the Ottoman Empire.

- The Commissar for Caucasian Affairs would assist the Armenians in the realization of these goals.

- A joint commission would be formed so Armenian lands could be evacuated of foreign troops.

Russian-German financial agreement of August 1918

In the wake of Russian repudiation of Tsarist bonds, nationalization of foreign-owned property and confiscation of foreign assets, the Russians and Germans signed an additional agreement on August 27, 1918. Russia agreed to pay six billion marks in compensation to German interests for their losses.

Lasting effects of the treaty

The Treaty of Brest-Litovsk lasted only eight and a half months. Germany renounced the treaty and broke diplomatic relations with RSFSR on November 5, 1918 because of Soviet revolutionary propaganda. The Ottoman Empire broke the treaty after just two months by invading the newly created Democratic Republic of Armenia in May 1918. Following the German capitulation, the Bolshevik legislature (VTsIK) annulled the treaty on November 13, 1918 (the text of the VTsIK Decision was printed in Pravda the next day). In the year after the armistice, the German Army withdrew its occupying units from the lands gained in the treaty, leaving behind a power vacuum that various forces subsequently attempted to fill. In the Treaty of Rapallo, concluded in April 1922, Germany accepted the Treaty's nullification, and the two powers agreed to abandon all war-related territorial and financial claims against each other.

The Treaty of Brest-Litovsk marked a significant contraction of the territory which the Bolsheviks controlled or could lay claim to as effective successors of the Russian Empire. While the independence of Finland and Poland was already accepted by them in principle, the loss of Ukraine and the Baltics created, from the Bolshevik perspective, dangerous bases of anti-Bolshevik military activity in the subsequent Russian Civil War (1918–20). Indeed, many Russian nationalists and some revolutionaries were furious at the Bolsheviks' acceptance of the treaty and joined forces to fight them. Non-Russians who inhabited the lands lost by Bolshevik Russia in the treaty saw the changes as an opportunity to set up independent states not under Bolshevik rule. Immediately after the signing of the treaty, Lenin moved the Soviet Russian government from Petrograd to Moscow.[6]

The fate of the region, and the location of the eventual western border of the Soviet Union, was settled in violent and chaotic struggles over the course of the next three and a half years. The Polish–Soviet War was particularly bitter and ended by the Treaty of Riga in 1921. Although most of Ukraine fell under Bolshevik control and eventually became one of the constituent republics of the Soviet Union, Poland and the Baltic states emerged as independent countries. This state of affairs lasted until 1939. As a consequence of the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact the Soviet Union advanced its borders westward by invading Poland and Finland in 1939, and annexing the Baltic States and Bessarabia in 1940. It thus overturned the territorial losses incurred at Brest-Litovsk.

For the Western Allies, the terms which the Germans imposed on the Russians were interpreted as a reminder and a warning of what to expect if the Germans and the other Central Powers won the war. Secret German archives found after 1945 proved that the German government and military intended to settle the conflict on harsh terms (especially against France and Belgium, whom they held responsible for damages after WWI). Between Brest-Litovsk and the point when the German military situation in the west became dire, some officials in the German government and high command began to favour offering more lenient terms to the Allies in exchange for their recognition of German gains in the east. In any event, Germany's treaty with the Bolsheviks spurred Allied efforts to win the war. One of the first conditions of the Armistice was the complete abrogation of the treaty.

Other information

Emil Orlik, the Viennese Secessionist artist, attended the conference, at the invitation of Richard von Kühlmann. He drew portraits of all the participants, along with a series of smaller caricatures. These were gathered together into a book, Brest-Litovsk, a copy of which was given to each of the participants.[7]

See also

- History of Belarus

- Mitteleuropa

- Treaty of Brest-Litovsk (February 9, 1918)

References

- ↑ Historia Polski 1795-1918 Andrzej Chwalba

- ↑ Czernin von und zu Chudenitz, Ottokar Theobald Otto Maria (1920). In the World War. New York and London: Harper & Brothers. Internet Archive, retrieved 28 February 2009.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Haffner, Sebastian (1988). Die Teufelspakt: Die Deutsch-Russischen Beziehungen Vom Ersten Zum Zweiten Weltkrieg. Manesse. ISBN 371758121X.

- ↑ John Keegan, The First World War (New York: Vintage Books, 2000), p. 342.

- ↑ Shirer, The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich, 1960, p. 57

- ↑ "LENINE’S MIGRATION A QUEER SCENE", The New York Times, March 16, 1918

- ↑ Emil Orlik(1870–1932) - Portraits of Friends and Contemporaries, accessed 24 August 2009

Further reading

- Kennan, George. Soviet Foreign Policy 1917-1941, Kreiger Publishing Company, 1960.

- Wheeler-Bennett, Sir John Brest-Litovsk the Forgotten Peace, March 1918, W. W. Norton & Company 1969.

External links

- Treaty of Brest-Litovsk (Yale University Avalon Project), including links to appendices.

|

||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||